In October I gave a talk at Monktoberfest in Portland, Maine, a small and intimate tech conference with a big impact in the industry. It’s quite unlike any other conference I’ve been to, which is explicitly the point. I’d been hearing about the conference from friends for years, and it somehow still managed to exceed all my lofty expectations.

Monktoberfest asks that your talk be something you wouldn’t be able to hear at any other conference. Mine was about values and how they show up at work and what happens when there is a gap between your stated and enacted values. It’s a theme that percolates through a lot of my writing and something I’ve spent many sleepless nights ruminating on, and giving this talk to such a receptive, empathetic, and compassionate audience was incredibly meaningful to me.

You can watch the talk here:

Seeing as I am personally allergic to watching any YouTube videos longer than five minutes unless I absolutely have to, I’ve also included a lightly edited version of the text of the talk below.

Before I start, I need to give the traditional disclaimer that this talk is reflective only of my personal views and not those of my employer. In fact, this talk is not reflective of the views of any of my employers, past or present, which is kinda the whole problem. Hi, I’m Jenny, I’m from Toronto, and it’s not important where I work.

I’m a software engineer, but I didn’t study computer science right out of high school. I had no idea what I wanted, and for some reason the advice people give to precocious try-hards who don’t know what they want is to go to business school. Business school and I did not get along. It was well into the twenty-first century and the career center was still giving advice on things like firm handshakes and skirt length. Not only was it extremely not my speed, it probably shouldn’t have been anyone’s speed.

I remember a resume-writing workshop where they told us to put our hobbies and sports and clubs on our resumes even if it seems irrelevant, because you never know whether someone else also played lacrosse or did model UN and will hire you for it. Which, if you think about job hunting as a zero-sum Thunderdome, isn’t inherently bad advice for a bunch of scared freshmen. The problem is that we also had to take a mandatory human resources class, and there was never a flip side about how maybe you shouldn’t hire someone just because they play the same golf course as you because that’s a stupid way to build a company.

(Just in case any future employers are watching reading this: I like roguelike video games, sci-fi and fantasy books, and rock climbing. Please hire me, I’m great at cosplaying capitalism.)

What my school was trying to do was give us a shortcut to culture fit, though they didn’t seem to particularly care if that landed us in a good culture. When hiring panels talk about culture fit, they’re really asking things like: could I be stuck at an airport with them? Could we get a beer together? In other words: do I like them? And we like people who have similar hobbies, went to similar schools, indulge in similar vices.

All of that, though, reinforces systemic biases and harms diversity. Long after HR bans you from only recruiting from the one elite university, cultural markers like sports and leisure can still sub in as a pretty reliable signifier of class and race. Not a lot of kids living in poverty play hockey in high school because hockey equipment is hella expensive.

Culture fit gatekeeping sucks! It sucks morally (and I’m taking for granted here that you agree with me that talent comes from everywhere and everyone deserve access to good jobs). It sucks for everyone who doesn’t have the right background or pedigree, because they’re the ones shut out due to culture fit. And frankly, it also sucks for the company. If a company isn’t hiring from most of the population, it’s straight up missing out on good talent.

Not to mention, that’s how companies lock into tunnel vision. Apple is currently being sued because AirTags are being used by stalkers and domestic abusers. This is as predictable as it is ghastly. The fact that AirTags were launched without thorough safety features means that a whole array of decision-makers, from engineers to product leads to managers to the board, looked at the product and said “yep seems fine”, and anyone who did sound the alarm about abuse risk was ignored. I would wager not a lot of those decision-makers have had stalkers.

So maybe culture fit isn’t a great search criteria for hiring decisions.

At the same time, every time I’ve looked for a job, the most important thing I look at is the company culture. We’ve all experienced toxic cultures; it is soul crushing. Whereas any job I have loved, I’ve loved because the culture was so great. I’ve been lucky in my career so far in that sometimes I get to be picky about where I work, and my choice always came down to culture.

I guess what I’m saying is, hiring someone to fit into a culture is bad, but interviewing for a culture you want to fit into is…good?

The problem here, of course, is that the word culture is extremely overloaded, and if you ask five people what they think culture means you’ll get six different answers. So let’s unpack that.

Culture is the norms and values of a community.

I like this definition because it turns something amorphous into a few distinct components:

- Norms are the things you do.

- Values are why you do it.

- And the community is who is included.

A norm describes a pattern of behaviour that’s taken for granted. You don’t really stop to think about the fact that you do it, until someone else doesn’t. People who stray from the norm are quickly nudged towards to the center, and they either adapt to it or risk consequences from the dominant group. A norm might be “we write engineering design docs for anything that will take longer than a week to build”, or “everyone should listen to customer calls, even if you don’t work in sales or support”. It could even be “we use commenters on Hacker News as a north star for our product development strategy”. (It shouldn’t be, but it could.)

Something being a norm doesn’t mean it’s good. An engineering team could have a norm of just retrying flaky tests until they pass, and everyone agrees that that’s bad, and we should probably get around to fixing those, but nothing happens, and new people are on-boarded into this being the normal way of behaving, and tests continue to flake like pastries.

A value is the thing we think of as being a capital-G Good thing. It’s the why, and it is inherently moral and prescriptive. It should be something that you’re willing to pay a cost to uphold, because not sticking to your value feels wrong somehow.

Your value could be “knowledge sharing through documentation”, which slows you down in the moment but makes your team stronger in the long term. Or it could be “ship early and often”, and the thought of polishing a product until it’s perfect instead of releasing early alphas and iterating is agonizing. A common value you see is “we don’t use tools that were not invented here”. I don’t have to agree with your values, but I can still tell that it’s the basis of something you hold dear.

How do norms and values impact “culture fit”? Well, looking at the specific way hiring for culture fit launders bias, what’s actually happening is that the org is looking for an alignment of norms. Systems want to perpetuate themselves, and they draw in people who will agree that the current way of doing things is normal. This includes tech stacks and testing philosophy at the relatively benign end, and “is this person one of us?” at the far end hiding all manner of sins.

The thing is, looking for norms isn’t just excluding people with different backgrounds. It’s also just not very useful. It doesn’t tell you all that much about what kind of person someone will be when the stakes are high and the pressure is on and you’re facing entirely novel problems. On the other hand, not only can people of all kinds of backgrounds have similar values, but core values are a much stronger foundation for figuring out what to do where there are no norms.

So. I suggest we think much less about culture fit, and much more about values alignment.

Unfortunately, values are kind of tricky to talk about. For one thing, personal values are sometimes so deeply held and so core to your understanding of the world that you might not even be able to name what they are. You just know in your gut when something doesn’t feel right.

Organizational values have the opposite problem, in that organizations are often more than happy to tell you all about their values, but it’s largely a marketing exercise. 55% of Fortune 100 companies cite “integrity” as a core value, and—I’m sorry, I read the business news—I know that’s nonsense. Companies talk about values to recruit talent, attract customers, and even claim the moral high ground against competitors (as the Wordpress community is finding out). We’ve all seen job postings from companies that say they value transparency but don’t want to tell you their salary ranges.

This quote is from a company that makes so-called productivity monitoring software.

![Our teams are 100% remote in support of the value we place on independent thought, creativity, and the freedom to work from anywhere in the world. In keeping with our mission and vision, we leverage the [software] internally, supporting work transparency and security balanced with trust.](/assets/img/2024-monktoberfest/slide3.jpeg)

The software lets employers install keyloggers and screen recorders on their employees’ machines. The software doesn’t make it clear to the employees that it’s surveilling everything they look at of course, but don’t worry, this is all in service of independent thought and trust.

ಠ_ಠ

So how can organizations look at values alignment when they don’t even know what they are?

It’s tempting to dismiss corporate values as being irrelevant when they’re so often co-opted for PR. But of course, organizations do still have values, often inherited from founders or early employees. They might be implicit and unspoken, and they may not be lit up in neon on company walls, but they’re deeply baked into the core assumptions of how decisions get made.

The funny thing about implicit values is that the folks inside are great at deducing what the organization actually values, regardless of what leadership says. They see first-hand the decisions being made and the behaviours that get rewarded and sanctioned. If teamwork is one of your company values, but there’s that one engineer who disappears into a cave for a few weeks or months at a time and comes back with 10,000 lines of code for a feature nobody asked for, and is then declared a genius and showered with accolades, you probably don’t actually value teamwork. If only firefighters get the glory, don’t be surprised if no one wants to work on asbestos removal.

When you’ve seen this disconnect between an organization’s stated and revealed values a few too many times, it’s easy to be jaded and think, oh I’m immune to this, this is just how it is. But even if you know intellectually that these disconnects exist, it can still be really damaging to trust when you’re actually confronted with specific examples of it happening.

I’ve worked in civic tech and non-profit and open source and all sorts of mission-driven spaces. I chose to work in these places because in my heart of hearts, I’m a huge softie and a true believer, no matter how much I try to be cynical about the improbability of ethical employment under capitalism. Hope springs eternal, and the manifesto said the right words, and I wanted to believe.

It didn’t always work out.

Increasingly there’s research that says that burnout isn’t just about working too much. It’s often much more about moral injury, a break with your values. It’s the psychic harm of not standing up for your beliefs, of watching unethical behaviour take place without doing something about it, of feeling betrayed by yourself or by someone you thought you trusted.

Like, imagine you had chosen to work at the ACLU because you really believed in its mission of protecting civil rights. And once you’re there, they turn around and hire the second-largest anti-union law firm in the country to union-bust. Turns out, civil rights didn’t include workers’ rights. The hurt left by this kind of betrayal lingers, and it cuts deepest for the people who believed in the mission the most, burns them out the hardest. When the gap between your stated values and your actual values becomes a chasm, the broken trust leaves a corrosive trail in your culture.

Whenever I’ve felt frustrated by this gap, what I really wanted to do was—metaphorically—shake the leadership and say to them: man, just admit you don’t actually care. Go install the analytics software that reports if your users are hovering 0.3 seconds over some button if you want, but stop pretending you care about privacy. You can run a company that doesn’t care about privacy, people do it all the time! But if that’s what you’re going to do, at least admit it.

As cathartic as that would be, it wouldn’t have actually accomplished anything, and not just because this is the opposite of effective communication and Marshall Rosenberg would be very disappointed in me. By and large, when I’m not fuming about the latest betrayal, I do believe that people mostly hold the values they say they do. Everyone is the hero of their own story, and everyone believes they’re acting with good intentions and making the best decision they can.

I get so mad because I’m thinking, why can’t people just do what they know is right? But honestly, is that so different from saying why can’t developers just stop writing insecure code? As we’ve painstakingly learned as an industry, you can’t improve a system by telling people to just be better at navigating the system. You need to make it hard for people to make mistakes, and you need to design the system in such a way that the right path is the easy path.

If values were easy to stick to even when the going got tough, they wouldn’t be values, they would be rationalizations. Your values should be the things you’re willing to pay a cost to uphold, even when it’s inconvenient or uncomfortable or expensive. People should have the moral courage to do the right thing. But they—we—often don’t. So then what?

If I’m at a WeWork by myself, I wear a mask. But if I’m coworking with a bunch of coworkers, and none of them are wearing masks, I’m also more likely to not wear one. I really do value public health, and sometimes I don’t value it more than I fear social ostracism. I don’t love this about myself, but it’s true. In 2020 and 2021 it was much easier to wear masks everywhere, because it was a much more prevalent behaviour. The individual cost of upholding public health has risen steeply since then.

But the fact that the cost of a moral choice can rise means it can also fall.

For example, many people value equitable compensation practices. When they find out their equally talented colleague who happens to be from a marginalized group makes less than they do, they’re genuinely upset. Some of those people might volunteer how much they make to arm their colleagues with bargaining info. But many people also wouldn’t. The social taboo against talking about money is huge, and if someone is paid significantly more than their peers, there can be all sorts of guilt and fear and shame wrapped up with that. They think, what if they get mad at me? What if I don’t deserve it? And so on. However, if you work with a bunch of people who regularly chat about compensation like it’s a no big deal, and everyone acknowledges that it’s a systemic problem and not an individual’s fault, that taboo starts to look less costly to break.

So, this is the work. The work of culture change is creating the conditions that make it easier to choose to do the right thing, to close the gap between your enacted values and your stated values.

If you’ve examined the values of your leaders and come to the conclusion that they truly hold different moral standards than you, then it’s time to leave, spiritually or literally. But sometimes, it’s not that you don’t share any values, it’s that it’s hard to stick to them. So make it easier.

Okay. Values are important. Gaps between stated values and revealed values destroy your culture. Sticking to your values is hard, so we need to change the culture to make it easier. So what are the levers available to you for making it easier?

Remember that culture is made up of norms and values. Norms are driven by values, but different values can arrive at the same behaviour. Let’s take the behaviour of writing documentation. In one org, that can be driven by the value of institutional knowledge sharing, and people write docs so they can share knowledge with their colleagues and their future selves and be assured that even if they leave, the knowledge doesn’t leave with them. In another org, the practice of documentation could be driven by the value that when something goes wrong, someone is to blame. (It’s a warped view of accountability, but I see it so often.) Documenting everything becomes the norm because everyone is trying to cover their butts and prove that there was nothing they could’ve done to prevent the incident, it’s that other team over there that didn’t do things correctly, and you can tell from the version history or whatever. These result in very different company cultures.

The fact that the same behavioural norm can have its roots in different value systems means that norms are easier to change than values. People are more willing to change their behaviour than their beliefs, because they can rationalize the new behaviour some other way until it becomes normal. And changing norms, in turn, makes it easier for others—who previously lacked the courage of their convictions—to make the right decision too.

But the fact that norms are easier to change than values also makes them more brittle.

In the aftermath of the George Floyd protests in 2020, companies rushed to issue statements that committed to Listening And Doing Better. They changed their display pictures, they set up ERGs, they appointed DEI leads. In the last eighteen months, after incredibly absurd fearmongering about the spectre of wokeness haunting America—frankly, I wish that were the case—and after sustained assault on trans rights and reproductive rights, we’re now watching companies roll back their DEI programs and lay off those teams and ban “political” conversation at work. For a moment, it seemed like caring about equity had a shot at becoming more normalized, especially at companies that wanted to attract top talent in a strong job market. But the norm was new and fragile, and it was still driven by the old underlying value of maximizing PR and minimizing blowback. Once the Overton window had been yanked far enough back to the right and a few hundred thousand layoffs had struck a blow against labour power, it was easy to reverse the norm before a new generation of workers who grew up with it come to expect it.

This is the catch-22 of culture change: fully integrating a new norm is difficult without changes in the underlying values, but values aren’t likely to change until the norms become normalized. Which means any culture change effort requires constant reinforcement to make sure the norms don’t regress before the values take hold.

So what does this work actually look like?

First, you gotta figure out what your organization’s values are.

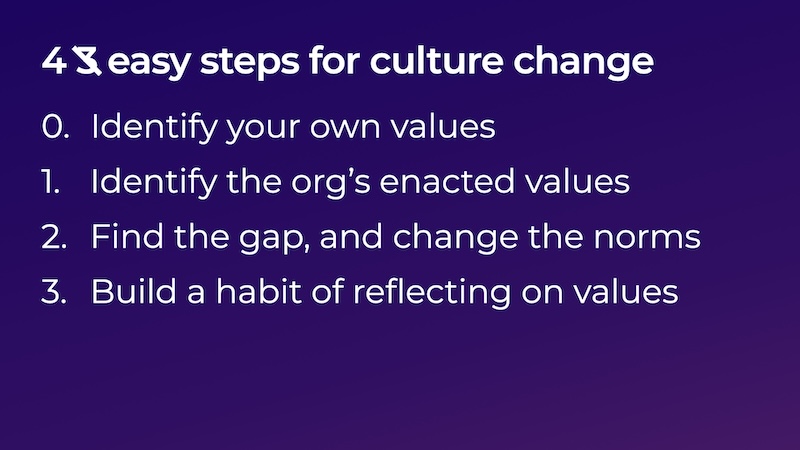

No, hang on. In this house we do zero-indexing.

Step zero, you gotta figure out what your own values are. I’m throwing this out there like it’s just a casual thing but it’s easier said than done. Introspection can be scary and unsettling, and I’m not going to stand up here and tell you there’s this one weird trick to discover your core values.

Although.

My startup hot take that I also deeply believe is that you shouldn’t be allowed to start a company until you’ve been to therapy.

Therapy obviously can’t fix everything, but it’s one of the few mechanisms we’ve developed as a society in which we can be guided to build self-awareness, reflect on who we want to be, and develop skills for handling emotionally fraught situations. Being a founder is an incredibly stressful, taxing, and often lonely job, and people understandably buckle under the stress and revert to their basest instincts. You owe it to the people who depend on you for their livelihoods to figure out your own baggage and learn some coping mechanisms before you start yelling in a meeting because someone asked a question in a tone that reminded you of your parents or whatever.

Go to therapy. Figure out your values in therapy!

Then step one is you figure out what your organization’s values are.

These are the ones that are currently enacted, not the ones you wish it held. Be brutally honest, even when it’s ugly and makes you squirm, and watch for places where your values have corrupted. Is your value of being deliberate in your decision-making leading to analysis paralysis? Do you care so much about being right that you’re treating every conversation like there has to be a winner and a loser? Ask the ICs what they think the organization embodies, and cross your fingers that there’s enough trust left that they will tell you the truth. Remember, we’re experts at differentiating between what our leaders say they value and what they actually value.

Once you’ve done that, step two is deciding which values are not the values you would want for your org.

If there’s a value you’d like to change or something that’s missing, look for the day-to-day structures and processes that are either reinforcing or preventing that value, and change those.

I know a social enterprise organization that had strong values of teamwork and collaboration, except for their cut-throat sales team. The sales team had the highest turnover in the whole company, and interactions had turned increasingly toxic. When leadership sat down and really looked at the problem, they realized that compensation was a key issue. Salespeople earned individual commissions, which was very normal, but this means they were motivated to hoard leads and hide information. So, despite initial pushback, the execs switched the compensation structure to collective commission: now the team as a whole got bonuses based on how much everybody sold. The new structure even included support staff like sales coordinators and admin. This not only meant that salespeople were incentivized to help each other with strategy instead of competing, but existing customers also got better service from the support team, who were now being rewarded if the account expanded. And the people who preferred to be cut-throat got fed up and left.

Individual commission is an incredibly normal practice, and I’m not saying it’s universally bad. For this particular org, that practice harmed the culture, and prevented it from growing. So, what is your version of a norm that’s stifling growth and pulling away from your values? And how can you find your equivalent of the collective commission?

So far all of this implicitly assumes you have some sort of leadership role in the organization. What do you do if you’re an IC?

ICs obviously have a huge part to play in a company’s culture, but I’ve sadly come to believe that changing the culture purely from the bottom up, with no top-down support, is impossible. This is because accountability and reinforcement are paramount. If leadership walks past bad behaviour or even rewards it, the new norms will not take root and you’ll regress to the mean. If you’re trying to get your team to take code reviews more seriously, and one or two people consistently merge stuff with just a rubber stamp and managers don’t care, gradually everyone will fall back into a cascade of LGTMs.

This sucks, right. I want to believe in the narrative of the little guy who took on the system and won. I want to be the Katniss Everdeen of organizational culture change, which is both possible and a normal thing to want.

And the thing is, once in a while, it does work. Once in a while the stars align, and the right person has the right kind of relationships and political capital and is willing to throw themselves on the pyre over and over again, and once in a while they get through. And so it’s tempting to think that that’s the way to go, because we have control over our individual effort in a way that we have control over very little else. But I don’t think that’s a scalable strategy, because the odds of success are so low and the risks are so high.

That’s the bad news. The good news is two-fold. One is that there are many different scopes for thinking about culture: at the project level, the team level, the office level, the division level. As an IC you may not be able to change what your entire company is like, but you do still have a lot of influence over your corner of the org, and carving out one corner of safety is absolutely not nothing.

The second bit of good news is that, in my experience, often leadership does know that there’s a problem, and they seem like they’re ignoring it not because they don’t care but because they have no idea what to do. And so, suggestions might be welcome! Sustaining culture change without leadership support is improbable, but enlisting leadership support for culture change isn’t. Talk to other ICs and gather consensus and bring your concerns and suggestions as a group. If you get dismissed, well, that’s honestly also pretty revealing about what your leadership actually values.

That said, this is exactly the kind of unpaid glue work that can be a huge strain for the people taking it on. It’s also work that often falls to marginalized employees, because for them it can be a matter of surviving in the organization. It’s deeply unfair that most organizations don’t reward this work, that you have less time to ship shiny features that get promotions if you’re fixing the culture. It is a thankless role, and I’m not saying you should volunteer as tribute. But if you have to do it, whether out of necessity or because you can’t help yourself, let’s find you friends in high places who can help.

Okay. Step three of culture change is to make reflecting on your values part of your regular rituals, the quarterly kick-off and the annual planning and the hiring plans and the performance evals.

You’re not going to adhere to your values perfectly, and that’s okay, but build a habit of reflecting on them. It’s easy to lose sight of how values start to drift amidst the chaos of running a business and brush it off as not being urgent enough to prioritize. so make it part of the norm of running the business.

You can never be fully values-aligned, and probably shouldn’t be. Your values are not your coworker’s values are not your manager’s values are not your CEO’s values, no matter how much they overlap. That tension is healthy, because values themselves are imperfect too, and dogmatic adherence to anything closes you off from learning. The important thing is to regularly negotiate and navigate that tension to make sure you as a group haven’t strayed too far from each other.

Now. A prerequisite for all of these steps is that you need to figure out how to solicit and listen to feedback.

The thing I would love for all leaders to recognize is that the expected return of going to leadership with negative feedback is terrible. Risk alienating your boss for the sake of telling the truth? Why? Even if you’re not directly retaliated against, and people often are, it can still really damage your standing. If you speak up too often, you’re branded as the naysayer. If you’re part of a marginalized group raising issues about how marginalized people are treated, you’re tarred as being “political” or “biased”. And of course, most of the time the canaries in the cultural coal mine are the marginalized employees with the least standing, because they’re the ones with the least protection when the cracks start to show.

If someone is speaking up despite all that, they’re speaking up because they genuinely want to help the organization get better. That means you have to learn how to hear the message even if it’s being delivered imperfectly, even angrily, by someone who feels hurt.

I’ve been part of several organizations that had leadership AMAs, and at each one of them, there were periods of time when the questions got kind of rude and mean. The organizations were struggling through a lot of rupture and change, and the people were struggling too. In each instance, the organization responded by reducing AMAs and imposing restrictions.

Now, I don’t even necessarily think that was in and of itself the wrong response; not all venues are suitable for all forms of feedback, and it’s definitely possible to accidentally amplify negativity in an unproductive way. But in none of the situations was it ever acknowledged that these grievances didn’t just spring into being fully formed one day. They were the culmination of people having tried to raise the alarm elsewhere over and over again and being ignored, and that frustration was now boiling over. Instead of recognizing that, there was a lecture about tone and civility, things moved on, the hurt festered, and people left.

One of the key skills leaders need in these situations is to recognize when they themselves are feeling defensive because they’re feeling cornered or attacked. This is so they can choose to not react in the moment. The power differential between leadership and ICs means that when leaders lash out it’s not just a momentary conflict, it’s a signal that this is not a safe place to provide feedback. Your team learns from that. When confronted with a tough piece of feedback, you don’t need to have an answer or solution in the moment. You do need to have the emotional awareness to acknowledge the risk your team took in giving you that feedback, appreciate that it was difficult to do, and take accountability for following up with a response once you’ve had time to reflect.

Again, go to therapy.

My final thought is this. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about values in the workplace, because whether I like it or not work is a huge part of our lives. Work doesn’t exist in a vacuum; the dynamics at work are microcosms of broader social patterns. And for me, at least, work feels like a place where I actually have a little bit of agency to effect change.

I said at the beginning that culture is the norms and values of a community. Thankfully we’re mostly past the collective delusion that work is family, but a workplace is still made up of people, and it is still a community of relationships.

This community can also be a network of care if you let it.

One thing that I find comfort in when I’m struggling with burnout from mismatched values, is stepping back from the fight with the institution and finding ways to invest in my coworkers instead. Changing the culture of an organization is really difficult, even with leadership buy-in. We can’t always change the conditions at work. But we can find joy in lifting each other up, in being supportive, in sharing triumphs and solidarity and, of course, so many memes.

The thing about values is that they are prescriptions of what you find good in the world, and what you will fight to preserve and advance. Whether you have those fights at work or beyond, your relationships will form the basis of change. Your culture is the water you swim in, and if you don’t actively, intentionally tend to it, you may not like what grows in the deep. Neglecting the role of values in your culture makes it harder to see when things start to fray, and these tears will continue to pull and rip in the dark until it’s too late to repair them. It is well worth doing the work to bring them out into the light.

Many thanks, as always, to my incredibly generous community of friends and colleagues who provided feedback. I do not have a lot of experience giving talks and had a lot of trouble putting this one together, and literally over a dozen people helped me along the way. You are all wonderful.